Etiology

Hemorrhagic infarctions (otherwise known as intracerebral hemorrhage or cerebral bleed) are the result of spontaneous hemorrhage within the brain. Underlying conditions that predispose to hemorrhagic infarctions include hypertension, aneurysms and brain tumors. Hemorrhagic infarctions differ from nonhemorrhagic infarctions (otherwise called ischemic infarctions), that are associated with the acute interruption of blood flow to an area within the brain.

Pathophysiology

The acute accumulation of blood within the brain leads to what is effectively a hematoma that causes an acute onset of symptoms secondary to the direct compression of the surrounding brain tissue. Compression of the brain tissue surrounding the hemorrhage leads to the subsequent disruption of the blood brain barrier. As a result vasogenic edema ensues secondary to an influx of water and proteins into the intracellular space. This typically occurs within 4-6 hours of the event and can continue for 3-5 days thereafter.

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs associated with hemorrhagic infarctions can include mentation changes, circling, and seizures for cerebral infarctions; hemi- or tetra paresis and cranial nerve deficits for brain stem infarctions; as well as vestibular signs for cerebellar infarctions. While the exact nature of the symptoms that occur vary with the location of the infarction, a key to the diagnosis is the acute nature of the onset of symptoms combined with the relative lack of progression shortly following their onset.

Diagnostic Tests

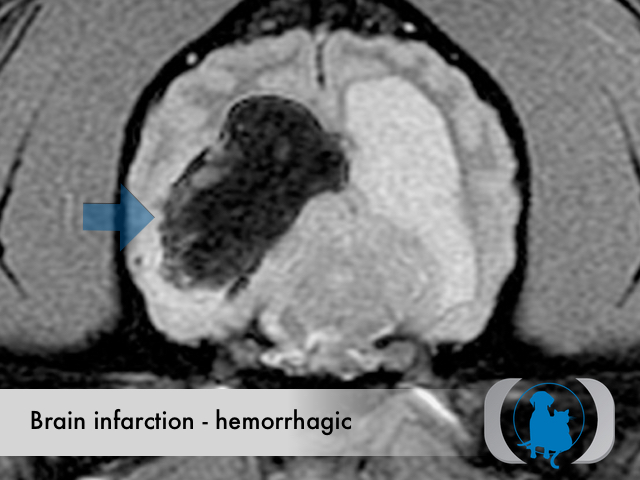

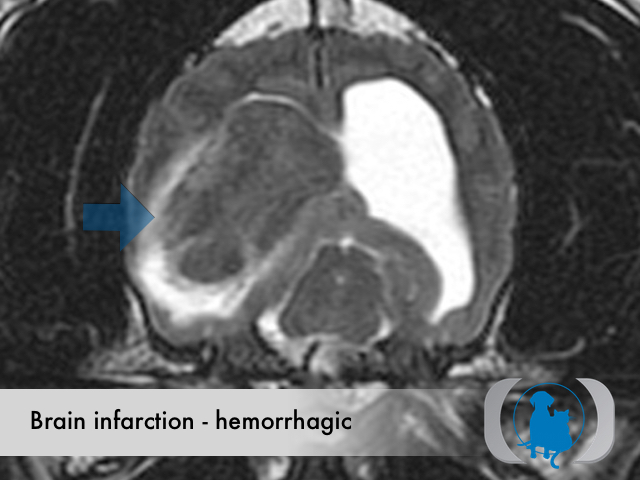

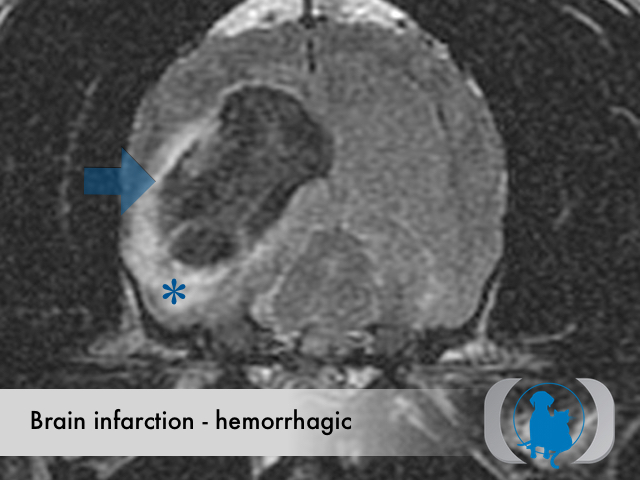

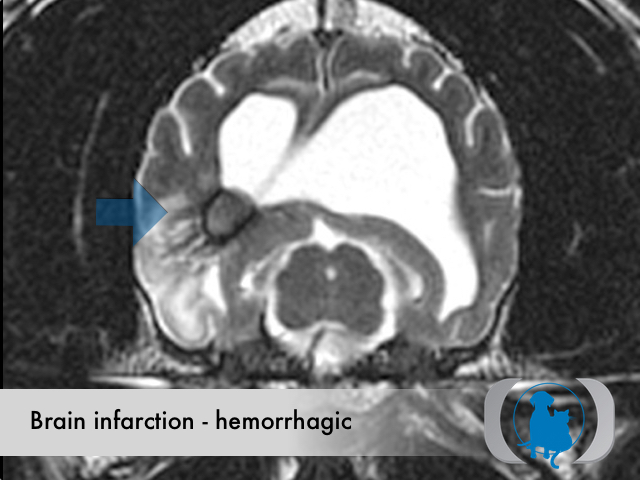

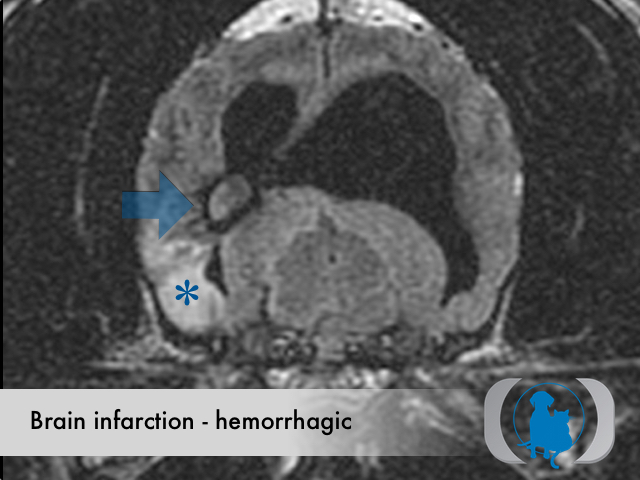

MRI is the diagnostic imaging modality of choice for diagnosing nonhemorrhagic infarctions. Hemorrhagic infarctions may demonstrate a variable signal intensity on MRI sequences based on the aging of the hemoglobin initially contained within the red blood cells.

In general, five stages of haematoma evolution are recognised:

- hyperacute

- intracellular oxyhemoglobin

- isointense on T1

- isointense to hyperintense on T2

- acute (1 to 2 days)

- intracellular deoxyhemoglobin

- T2 signal intensity drops (T2 shortening)

- T1 remains intermediate-to-low

- early subacute (2 to 7 days)

- intracellular methemoglobin

- T1 signal gradually increases (T1 shortening) to become hyperintense

- late subacute (7 to 14-28 days)

- extracellular methemoglobin: over the next few weeks, as cells break down, extracellular methemoglobin leads to an increase in T2 signal

- chronic (>14-28 days)

- periphery

- intracellular hemosiderin

- low on both T1 and T2

- center

- extracellular hemichromes

- isointense on T1, hyperintense on T2

- periphery

GRE T2* images are very sensitive to hemorrhage with blood appearing markedly hypointense.

Therapy

Therapy for hemorrhagic infarctions includes largely symptomatic therapy for seizures and the potential concurrent ataxia and paresis that may occur pending the location of the infarction. When possible, therapy directed at the cause of the infarction (e.g., hypertension) should be pursued. Unfortunately in most cases of hemorrhagic infarction in dogs and cats, the underlying cause for the infarction is not identified.

Image Gallery